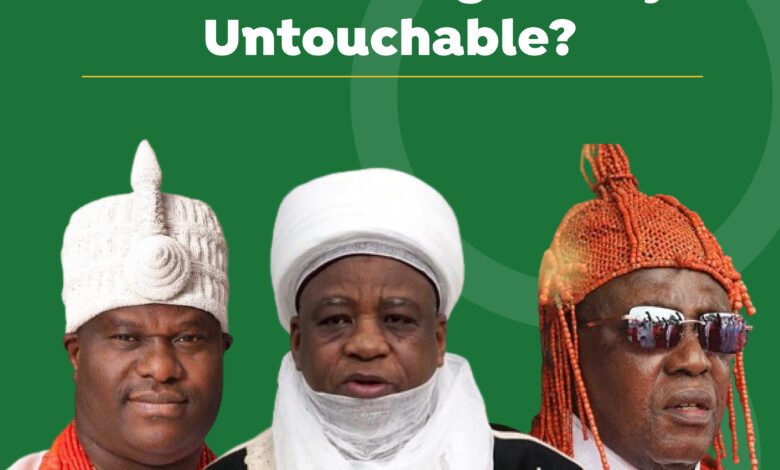

Recent events in Kano have reignited a crucial debate: are there truly “untouchable” traditional rulers in Nigeria who are above the law?

Kano, once a revered symbol of Northern Nigerian royalty, has become a battleground for political intrigue.

The chain of events in the past days highlights the complex relationship between Nigeria’s democratic constitution, which guarantees equality and accountability, and its rich cultural heritage, where monarchs often hold a seemingly untouchable status.

Constitution vs Culture

Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution is clear: all citizens are equal and accountable under the law. Section 17 enshrines the principles of equality and justice, while Section 42 prohibits discrimination. The constitution establishes institutions like the judiciary and law enforcement to uphold these principles.

Traditional monarchs, from the Ooni of Ife to the Sultan of Sokoto, hold immense cultural and symbolic significance. They embody the history, customs, and values of their ethnicities. In many cases, they are seen as sacred figures, wielding influence beyond their traditional domains.Despite the constitution’s emphasis on equality, cultural norms often shield traditional rulers from criticism, scrutiny, and even legal consequences. This perception of “untouchability” stems from a blend of historical, religious, and social factors. Some monarchs are believed to possess spiritual powers, making them inviolable. Others wield considerable political and economic influence, granting them perceived immunity.

Demystifying the Monarchy

Over time, this tension between constitutional provisions and cultural practices has led to controversies and challenges. History reveals instances where the government has asserted its authority over supposedly powerful monarchs.

In 1996, the military regime under Sani Abacha forcefully deposed Ibrahim Dasuki, the 18th Sultan of Sokoto, demonstrating that even highly esteemed figures are not exempt from the government’s reach.

Similarly, the notion of an “untouchable” Alaafin of Oyo in Southwest Nigeria was challenged. In what appeared to be a politically motivated move, former Oyo State Governor Otunba Adebayo Alao-Akala stripped the Alaafin, Oba Lamidi Adeyemi, of his permanent chairmanship of the Oyo State Council of Chiefs and Obas.

Another former Oyo Governor, Abiola Ajimobi also challenged the old order as he moved to weaken the powers of the Olubadan.

The late Ajimobi was unequivocal about his ability to depose the Olubadan at the time but he said he would not take the option.

“All the relevant sections of the 1959 chieftaincy declarations are very clear on the powers of the governor viz-a-viz the traditional rulers and the administration and particularly sections 26 and 27 empowers the governor to sanction any erring oba,” he boasted.

“Who bestowed the crown and staff of office on the monarch? Is it not the government? But you see, when a person is in a position as such, he shouldn’t wield his powers every time, particularly against someone who one claims to be his father.

“I have found enough reasons to depose him, but I will never do it. If he likes, let him go to the radio or television to abuse me, I don’t care and I will never use that against him.”

He stressed that “no one is above the law” and that everyone must adhere to the established legal framework.

Former President Olusegun Obasanjo echoed similar sentiments while addressing Traditional rulers at a function in September 2023 as captured by Tribune Newspapers.

He said: “Please in Yoruba land, there are two things that are most respected among others: age and position. A governor’s position is more powerful than that of any king when he is still in power.”

This superiority of Governors also played out when Oba Adesina Adepoju, Deji of Akure was also deposed by the Ondo state government for assaulting one of the late wives in public in 2010 by Olusegun Mimiko’s government.

These events highlight a crucial point: cultural reverence cannot shield monarchs from legal consequences or political challenges. While the Ooni of Ife or the Oba of Benin may be seen as untouchable due to their heritage, history shows that this perception has limits, especially when the government has sufficient cause for action.